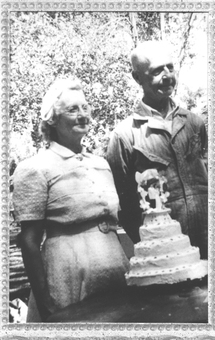

I went to my Grandmother’s 100th birthday party family reunion in 1994, along with one hundred and thirty-four of my closest relatives (Grandma had 11 children, who all had children, who all had children, etc.). There was food, dancing, singing, playing games, prizes, and a great big party. On the last day of the reunion, my immediate family and assorted nieces and nephews drove out to Grandma’s farm, 22 miles out onto the prairies where15 year old Grandma married her 35 year old schoolteacher husband long, long ago; where the silvery barn cupola is scratched with the names of my brothers and sisters and uncles and aunts and cousins and second cousins and so on back to time more than 70 years ago(then) when the barn was first built.

We all went into the farmhouse. The door wasn’t even locked. We went upstairs, where I remember being buried in the wintertime, years ago, under PILES of old wool quilts to keep us warm, because the only heat upstairs came through the grates from the wood stove down below. Those quilts were HEAVY, and wool, and UGLY, too. One of those old quilts was still there, so I know for sure. I found an old picture of me when I was two in the top drawer of an old wooden bureau, with my name and the date written on the back in Grandma’s spidery hand. It really touched me to know that that picture of me must have mattered to her enough to be kept for 41 years out there on the windblown plains, where few frills survive.

We went downstairs, and in the hall closet was an old quilt, made from the pattern I remember being on my mother’s bed when I was small. It isn’t a “Trip Around the World,” and it’s not a “Log Cabin,” and it isn’t “Double Irish Chain,” or even a “Grandmother’s Flower Garden.” It isn’t any pattern I’ve ever seen anywhere else, but I know it. I know it with the heart and soul and hands of anyone who ever put two pieces of cloth together.

I didn’t get a home run in the baseball game. I didn’t win the talent contest. I didn’t even win the prize for getting the most signatures of relatives; but I did get a prize, the best prize of all. I got Grandma’s quilt, made from the aprons she wore, and my uncles’ shirts and my aunts’ dresses. It’s old now, but so what if it’s a little faded and a little bit worn? Many of the prints are still bright, it’s hand quilted in my Grandma’s distinctive style, but more importantly, it’s a connection. It’s a linking of myself and my mother and grandmother and great-grandmother and the great beyond. We all sew, we all mix fabric and color and stolen time to make quilts “as fast as we can to keep our children warm, and as pretty as we can so our hearts don’t break.”[1] That’s what quilting is all about, that’s what we’re here for.

These old quilts that are part of our lives, made from traditional patterns that have been done and done again, are precious to me. I don’t make traditional quilts much, anymore, but that doesn’t mean I don’t value them. I do make traditional patterns whenever I want the illusion that I have some control over my environment, and just because a person tends to use paints and dyes and raw edges and machine appliqué and quilting DOES NOT mean they don’t value traditional methods and ways. Quilters aren’t people who throw the baby out with the bathwater; they wrap the baby in love and patches, and treasure each drop of the bathwater, each tiny stitch and faded pattern. Contemporary quilt artists work in new patterns, they see a further dimension, they push the envelope as far as they can and still be fiber artists, but that’s okay, because they still base their work on the quilts your mother made, and your grandmother, and mine.

Grandma died on September 19, 1995. The last story I heard about her was from my sister, Marie, who said she went out there that summer when Grandma was still doing fine, tatting and quilting and playing cards, and VERY proud of the fact that she was “one hundred and one - and a HALF!” She would have been 102, come January, and I’m sorry she didn’t quite make it. It just goes to show you, though, that Garrison Keillor was right when he said that where we come from, “All the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

We went downstairs, and in the hall closet was an old quilt, made from the pattern I remember being on my mother’s bed when I was small. It isn’t a “Trip Around the World,” and it’s not a “Log Cabin,” and it isn’t “Double Irish Chain,” or even a “Grandmother’s Flower Garden.” It isn’t any pattern I’ve ever seen anywhere else, but I know it. I know it with the heart and soul and hands of anyone who ever put two pieces of cloth together.

I didn’t get a home run in the baseball game. I didn’t win the talent contest. I didn’t even win the prize for getting the most signatures of relatives; but I did get a prize, the best prize of all. I got Grandma’s quilt, made from the aprons she wore, and my uncles’ shirts and my aunts’ dresses. It’s old now, but so what if it’s a little faded and a little bit worn? Many of the prints are still bright, it’s hand quilted in my Grandma’s distinctive style, but more importantly, it’s a connection. It’s a linking of myself and my mother and grandmother and great-grandmother and the great beyond. We all sew, we all mix fabric and color and stolen time to make quilts “as fast as we can to keep our children warm, and as pretty as we can so our hearts don’t break.”[1] That’s what quilting is all about, that’s what we’re here for.

These old quilts that are part of our lives, made from traditional patterns that have been done and done again, are precious to me. I don’t make traditional quilts much, anymore, but that doesn’t mean I don’t value them. I do make traditional patterns whenever I want the illusion that I have some control over my environment, and just because a person tends to use paints and dyes and raw edges and machine appliqué and quilting DOES NOT mean they don’t value traditional methods and ways. Quilters aren’t people who throw the baby out with the bathwater; they wrap the baby in love and patches, and treasure each drop of the bathwater, each tiny stitch and faded pattern. Contemporary quilt artists work in new patterns, they see a further dimension, they push the envelope as far as they can and still be fiber artists, but that’s okay, because they still base their work on the quilts your mother made, and your grandmother, and mine.

Grandma died on September 19, 1995. The last story I heard about her was from my sister, Marie, who said she went out there that summer when Grandma was still doing fine, tatting and quilting and playing cards, and VERY proud of the fact that she was “one hundred and one - and a HALF!” She would have been 102, come January, and I’m sorry she didn’t quite make it. It just goes to show you, though, that Garrison Keillor was right when he said that where we come from, “All the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”